Storage in Ethereum

The Ethereum blockchain’s storage concepts are complex. Merkle Patricia trees are used to store data efficiently, and they provide instant and complete verifiability. While Merkle Patricia trees present challenges with reading and storing data, other storage problems also need to be handled. For example:

- How do we handle storage modifications made by failed Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) execution?

- How should the EVM access Merkle Patricia tree storage?

- When and where should we commit storage modifications?(after transaction execution, after block finalisation, after multiple blocks/transactions etc.)

- How can we optimally access permanent storage and commit changes to disk?

- How do we handle invalid blocks that failed validation?

In this post, I’ll describe how we’re solving these challenges in the Mana-Ethereum project. I won’t go into detail on Merkle Patricia trees as there is a lot of information about these already in the community. I will cover high-level storage access, and approaches to solving difficult storage issues.

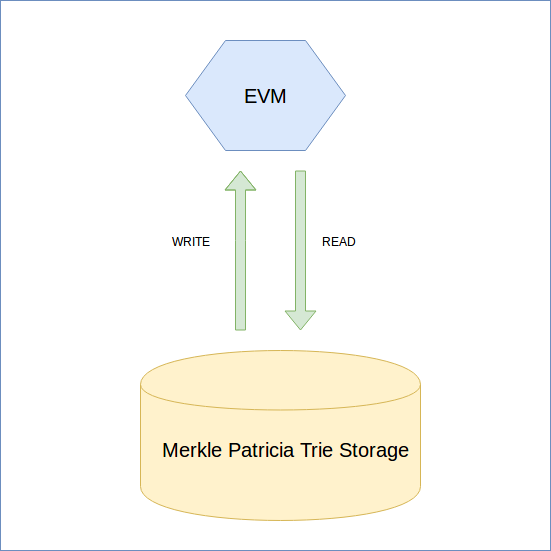

Naive approach

The naive storage approach is to use the Merkle Patricia Trie directly in the EVM and to make all changes to the database during its execution. However, an issue arises with failed EVM executions. How do we handle these failures?

One solution is to keep all the data in Merkle Patricia trie storage. We don’t delete anything. Merkle Patricia tries are defined by their root hash, so if we don’t delete any data from the permanent storage we can always return to any root hash that has ever existed in the database. If the EVM execution fails, we can return to the root hash that existed before the failure. While this approach can work, it results in an extremely slow and inefficient storage process.

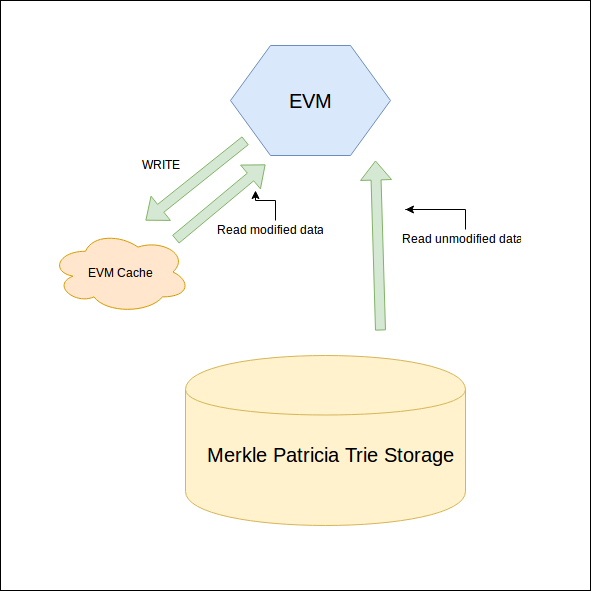

Cache storage for EVM execution

We can improve on our initial approach by introducing a simple in-memory cache designed to store modifications that happen during EVM execution. All data is read from the permanent Merkle Patricia trie storage, but all modifications are committed to in-memory storage. This in-memory cache can be much simpler than the Merkle tree data structure, and speeds up EVM operations that write data to storage. Merkle Patricia trie updates are quite expensive, and using in-memory cache is much more efficient than traversing the entire Merkle trie for every storage operation.

If we use an in-memory EVM cache, when should we commit these modifications from the cache to storage? To answer this question, we need to look at the transaction receipt. The transaction receipt is a data structure that contains information about the executed transaction (used gas etc). It also contains the state root hash that exists immediately after transaction execution (for pre-Byzantium blocks). So we have to commit changes after we receive the transaction receipt (which contains the state root hash from the Merkle Patricia trie storage).

Unfortunately, there is a problem with this approach.

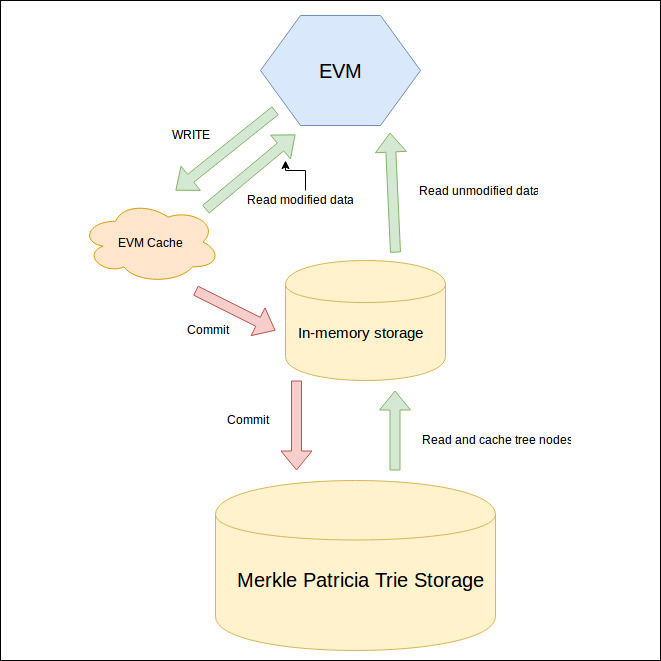

Cache storage for blocks

The problem with the previous approach is that we should commit the cache after every transaction. That works if we’re only importing valid blocks. But in the real network, some peers will share invalid blocks and we shouldn’t commit changes made in those transactions.

To fix this, we introduce a second cacheing level. We can use an in-memory trie where transaction changes are committed from the EVM cache. It solves the invalid data problem because we simply discard in-memory tries from invalid blocks.

An in-memory trie will read non-existing in-memory nodes from permanent disk storage and it will write all changes to memory. Another optimization we get from the in-memory trie is that update/read speed is much faster from memory than from disk.

We can choose to commit changes from in-memory trie storage after every valid block or after multiple valid blocks.

Optimisations

Several more optimisations make working with storage even faster:

- Batch updates. We can use batch updates when committing modified data to the permanent storage.

- Single trie traversal. We can commit in-memory trie changes by dumping all modified nodes from a single trie to the permanent storage. This saves us from traversing the second tree to update raw key-value pairs.

Conclusion

The final memory model (cache storage for blocks) is what we’re using in the Mana-Ethereum project. We are moving to it step by step and improving it along the way. We’ve learned a lot about memory storage as we go, and I hope this post will be useful for anyone implementing an Ethereum client.

Comments